Search

Gold certificate (United States)

Gold certificates were issued by the United States Treasury as a form of representative money from 1865 to 1933. While the United States observed a gold standard, the certificates offered a more convenient way to pay in gold than the use of coins. General public ownership of gold certificates was outlawed in 1933 and since then they have been available only to the Federal Reserve Banks, with book-entry certificates replacing the paper form.

Overview

Gold certificates were first authorized under the Legal Tender Act of 1863, but unlike the United States Notes also authorized, they apparently were not printed until 1865. The need for them arose from the limitations of the United States Notes. To promote the flow of gold into the Treasury and maintain the credit of the government, the notes could not be used to pay customs duties or interest on the federal debt. Gold certificates, representing coins held physically in the Treasury, were instead provided for those purposes. The notes, as legal tender for most purposes, were the dominant paper currency until 1879 but were accepted at a discount in comparison to the gold certificates. After 1879 the government started to redeem United States Notes at face value in gold, bringing them into parity with gold certificates and making the latter also a candidate for general circulation.

The first gold certificates had no series date; they were hand-dated and payable either to the bearer or to the order of a named payee. They featured a vignette of an eagle uniformly across all denominations. Later issues (series 1870, 1871, and 1875) featured portraits of historical figures. The reverse sides were either blank or featured abstract designs. The only exception was the $20 of 1865, which had a picture of a $20 gold coin. The Series of 1882 was the first series that was uniformly payable to the bearer; it was transferable and anyone could redeem it for the equivalent in gold. This was the case with all gold certificate series from that point on, with the exception of 1888, 1900, and 1934. The series of 1888 and 1900 were issued to specific payees as before. The series of 1882 had the same portraits as the series of 1875, but a different back design, featuring a series of eagles, as well as complex border work.

Historic U.S. gold certificates (1863–1933)

Gold certificates, along with all other U.S. currency, were made in two sizes—a larger size from 1865 to 1928, and a smaller size beginning with the series of 1928. The backs of all large-sized notes (and also the small-sized notes of the Series of 1934) were orange, resulting in the nickname "yellow boys" or "goldbacks". The backs of the Series of 1928 bills were green, and identical to the corresponding denomination of the more familiar Federal Reserve Notes, including the usual buildings on the $10 through $100 designs and the less-known abstract designs of denominations $500 and up. Both large and small size gold certificates feature a gold treasury seal on the obverse, just as U.S. Notes feature a red seal, silver certificates (except World War II Hawaii and North Africa notes) a blue seal, and Federal Reserve Notes a green seal.

In the case of the Series 1928 (small-size) gold certificates, they bore a redemption statement with the following text: "This certifies that there have been deposited in the Treasury of the United States of America XXXXX Dollars in Gold Coin payable to the bearer on demand."

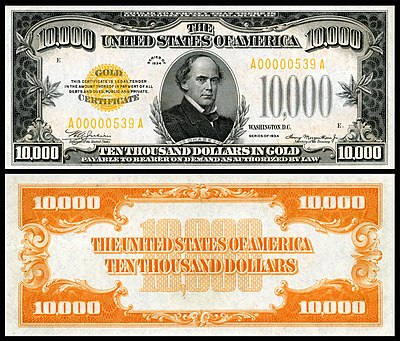

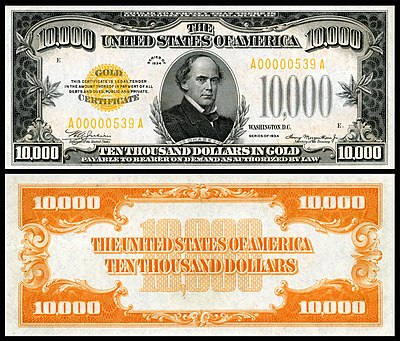

Series of 1900 $10,000 Gold Certificates

Another interesting note is the Series of 1900. Along with the $5,000 and $10,000 of the Series of 1888, all 1900 bills ($10,000 denomination only) have been redeemed, and no longer have legal tender status. Most were destroyed, with the exception of a number of 1900 $10,000 bills that were in a box in a post office near the U.S. Treasury in Washington, D.C. There was a fire on December 13, 1935, and employees threw burning boxes out into the street. The box of canceled high-denomination currency burst open. Much to everyone's dismay, they were worthless. There are several hundred outstanding, and their ownership is technically illegal, as they are stolen property. However, due to their lack of intrinsic value, the government has not prosecuted any owners, citing more important concerns. They carry a collector value in the numismatic market and, as noted in Bowers and Sundman's The 100 Greatest American Currency Notes, the only United States notes that can be purchased for less than their face value. This is the only example of "circulating" U.S. currency that is not an obligation of the government, and thus not redeemable by a Federal Reserve Bank. The note bears the portrait of Andrew Jackson and has no printed design on its reverse side.

End of the Gold Certificate Era in the United States (March 1933)

As part of the Roosevelt Administration's response to the effects of the Great Depression and particularly the outflow of gold for hoarding and for shipment overseas, the practice of redeeming gold certificates for gold coin was ended by Presidential Proclamation 2039 (dated March 6, 1933) and Executive Order 6073 (dated March 10, 1933). On April 5, 1933, Executive Order 6102 was issued; it required all persons in the United States to deliver (with limited exceptions) all gold coin, gold bullion, and gold certificates to the Federal Reserve by May 1, 1933. By order of the Secretary of the Treasury dated December 28, 1933, private possession of gold certificates was declared illegal. Due to their (then-) illegal status and public fear that the notes would be devalued and made obsolete, this resulted in the majority of circulating notes being retired.

The restrictions on private ownership of gold certificates were revoked by Treasury Secretary Douglas Dillon effective April 24, 1964, primarily to allow collectors to own examples legally; however, gold certificates are no longer redeemable for gold, but instead can be exchanged at face value for other U.S. coin and currency designated as legal tender (e.g., Federal Reserve Notes and United States Notes). In general, the notes are scarce and valuable, especially examples in "new" condition.

Series of 1934 Gold Certificates; Modern usage by the Federal Reserve System

The Gold Reserve Act of 1934 established a new accounting mechanism, through the issue of a special series of gold certificates, to account for gold held by the Federal Reserve Banks on behalf of the United States. The Secretary of the Treasury is authorized to "prescribe the form and denominations of the certificates".

The Series of 1934 (bearing the signatures of William Alexander Julian (Treasurer) and Henry Morgenthau (Treasury Secretary)) consisted of the following denominations: $100; $1,000; and $10,000 (mirroring the circulating Federal Reserve Notes of the same series and denominations). However, there was also a $100,000 denomination (bearing the portrait of President Woodrow Wilson) that had no equivalent in other types of U.S. currency and was also the largest currency denomination ever issued by the United States Treasury. 42,000 of the $100,000 denomination were printed. According to the Bureau of Engraving and Printing's own website, the $100,000 certificates were printed between December 18, 1934, and January 9, 1935. These notes were never intended for circulation in the general economy and there are no known instances of any such certificates ever being released outside government channels, other than as specimens such as one recently graded by PMG.

Reflecting the purpose for which these certificates were issued, the redemption statement on their face was changed to read as follows: "This certifies that there is on deposit in the Treasury of the United States of America XXXXX Dollars in Gold payable to bearer on demand as authorized by law."

Since the 1960s, most of the paper certificates have been destroyed, and the currently prescribed form of the "certificates" issued to the Federal Reserve is an electronic book entry account between the Federal Reserve and the Treasury. The electronic book entry system also allows for the various regional Federal Reserve Banks to exchange certificate balances among themselves. However, the Treasury authorized a small amount of them to be retained at certain Federal Reserve Banks (where they had been used) for educational and historical purposes, such as being placed on public display. In addition, a $100,000 Series of 1934 gold certificate is part of the numismatic collection at the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History.

As of December 2013 the Federal Reserve reported holding $11.037 billion (face value) of these certificates. The Treasury backs these certificates by holding an equivalent amount of gold at the statutory exchange rate of $42 2/9 per troy ounce of gold, though the Federal Reserve does not have the right to exchange the certificates for gold. As the certificates are denominated in dollars rather than in a set weight of gold, any change in the statutory exchange rate towards the (much higher) market rate would result in a windfall accounting gain for the Treasury.

Series and varieties

Complete United States gold certificate type set

Large

Small

Series catalogue

This is a chart of some of the series of gold certificates printed. Each entry includes: series year, general description, and printing figures if available.

Small-size gold certificates

* Notes: All Series 1928A gold certificates were consigned to destruction and never released; none are known to exist.

See also

- Silver certificate (United States)

- National gold bank note

- Digital gold currency

Footnotes

Notes

References

- Friedberg, Arthur L.; Friedberg, Ira S. (2013). Paper Money of the United States: A Complete Illustrated Guide With Valuations (20th ed.). Coin & Currency Institute. ISBN 978-0-87184-520-7. Retrieved February 14, 2014.

Text submitted to CC-BY-SA license. Source: Gold certificate (United States) by Wikipedia (Historical)

Articles connexes

- United States one hundred-thousand-dollar bill

- Silver certificate (United States)

- Large denominations of United States currency

- Gold as an investment

- Music recording certification

- Bank of England £100,000,000 note

- United States one-hundred-dollar bill

- RIAA certification

- Executive Order 6102

- United States fifty-dollar bill

- History of the United States dollar

- United States ten-dollar bill

- Gold Reserve Act

- United States dollar

- Series (United States currency)

- Banknotes of the United States dollar

- United States Bullion Depository

- Awards and decorations of the United States government

- List of presidents of the United States on currency

- 2024 United States presidential election

Owlapps.net - since 2012 - Les chouettes applications du hibou