Search

François Villon

François Villon (Modern French: [fʁɑ̃swa vijɔ̃], Middle French: [frãːˈswɛ viˈlõː]; c. 1431 – after 1463) is the best known French poet of the Late Middle Ages. He was involved in criminal behavior and had multiple encounters with law enforcement authorities. Villon wrote about some of these experiences in his poems.

Biography

Birth

Villon was born in Paris in 1431. One source gives the date as 19 April, 1432 [O.S. April 1, 1431].

Early life

Villon's real name may have been François de Montcorbier or François des Loges: both of these names appear in official documents drawn up in Villon's lifetime. In his own work, however, Villon is the only name the poet used, and he mentions it frequently in his work. His two collections of poems, especially "Le Testament" (also known as "Le grand testament"), have traditionally been read as if they were autobiographical. Other details of his life are known from court or other civil documents.

From what the sources tell us, it appears that Villon was born in poverty and raised by a foster father, but that his mother was still living when her son was thirty years old. The surname "Villon," the poet tells us, is the name he adopted from his foster father, Guillaume de Villon, chaplain in the collegiate church of Saint-Benoît-le-Bétourné and a professor of canon law, who took Villon into his house. François describes Guillaume de Villon as "more than a father to me".

Student life

Villon became a student in arts, perhaps at about twelve years of age. He received a bachelor's degree from the University of Paris in 1449 and a master's degree in 1452. Between this year and 1455, nothing is known of his activities. The Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition (1910–1911) says "Attempts have been made, in the usual fashion of conjectural biography, to fill up the gap with what a young graduate of Bohemian tendencies would, could, or might have done, but they are mainly futile."

Alleged criminal activities

On 5 June 1455, the first major recorded incident of his life occurred. While in the Rue Saint-Jacques in the company of a priest named Giles and a girl named Isabeau, he met a Breton named Jean le Hardi, a Master of Arts, who was also with a priest, Philippe Chermoye (or Sermoise or Sermaise). A scuffle broke out and daggers were drawn. Sermaise, who is accused of having threatened and attacked Villon and drawn the first blood, not only received a dagger-thrust in return, but a blow from a stone, which struck him down. He died of his wounds. Villon fled, and was sentenced to banishment – a sentence which was remitted in January 1456 by a pardon from King Charles VII after he received the second of two petitions which made the claim that Sermaise had forgiven Villon before he died. Two different versions of the formal pardon exist; in one, the culprit is identified as "François des Loges, autrement dit Villon" ("François des Loges, otherwise called Villon"), in the other as "François de Montcorbier." He is also said to have named himself to the barber-surgeon who dressed his wounds as "Michel Mouton." The documents of this affair at least confirm the date of his birth, by presenting him as twenty-six years old or thereabouts.

Around Christmas 1456, the chapel of the Collège de Navarre was broken open and five hundred gold crowns stolen. Villon was involved in the robbery. Many scholars believe that he fled from Paris soon afterward and that this is when he composed what is now known as the Le Petit Testament ("The Smaller Testament") or Le Lais ("Legacy" or "Bequests"). The robbery was not discovered until March of the next year, and it was not until May that the police came on the track of a gang of student-robbers, owing to the indiscretion of one of them, Guy Tabarie. A year more passed, when Tabarie, after being arrested, turned king's evidence and accused the absent Villon of being the ringleader, and of having gone to Angers, partly at least, to arrange similar burglaries there. Villon, for either this or another crime, was sentenced to banishment; he did not attempt to return to Paris. For four years, he was a wanderer. He may have been, as his friends Regnier de Montigny and Colin des Cayeux were, a member of a wandering gang of thieves.

Le Testament, 1461

The next date for which there are recorded whereabouts for Villon is the summer of 1461; Villon wrote that he spent that summer in the bishop's prison at Meung-sur-Loire. His crime is not known, but in Le Testament ("The Testament") dated that year he inveighs bitterly against Bishop Thibault d'Aussigny, who held the See of Orléans. Villon may have been released as part of a general jail-delivery at the accession of King Louis XI and became a free man again on 2 October 1461.

In 1461, he wrote his most famous work, Le Testament (or Le Grand Testament, as it is also known).

In the autumn of 1462, he was once more living in the cloisters of Saint-Benoît.

Banishment and disappearance

In November 1462, Villon was imprisoned for theft. He was taken to the Grand Châtelet fortress that stood at what is now Place du Châtelet in Paris. In default of evidence, the old charge of burgling the College of Navarre was revived. No royal pardon arrived to counter the demand for restitution, but bail was accepted and Villon was released. However, he fell promptly into a street quarrel. He was arrested, tortured and condemned to be hanged ("pendu et étranglé"), although the sentence was commuted to banishment by the parlement on 5 January 1463.

Villon's fate after January 1463 is unknown. Rabelais retells two stories about him which are usually dismissed as without any basis in fact. Anthony Bonner speculated that the poet, as he left Paris, was "broken in health and spirit." Bonner writes further:

He might have died on a mat of straw in some cheap tavern, or in a cold, dank cell; or in a fight in some dark street with another French coquillard; or perhaps, as he always feared, on a gallows in a little town in France. We will probably never know.

Works

Le Petit Testament, also known as Le Lais, was written in late 1456. The work is an ironic, comic poem that serves as Villon's will, listing bequests to his friends and acquaintances.

In 1461, at the age of thirty, Villon composed the longer work which came to be known as Le grand testament (1461–1462). This has generally been judged Villon's greatest work, and there is evidence in the work itself that Villon felt the same.

Besides Le Lais and Le grand testament, Villon's surviving works include multiple poems. Sixteen of these shorter poems vary from the serious to the light-hearted. An additional eleven poems in thieves' jargon were attributed to Villon from a very early time, but many scholars now believe them to be the work of other poets imitating Villon.

Discussion

Villon was a great innovator in terms of the themes of poetry and, through these themes, a great renovator of the forms. He understood perfectly the medieval courtly ideal, but he often chose to write against the grain, reversing the values and celebrating the lowlifes destined for the gallows, falling happily into parody or lewd jokes, and constantly innovating in his diction and vocabulary; a few minor poems make extensive use of Parisian thieves' slang. Still Villon's verse is mostly about his own life, a record of poverty, trouble, and trial which was certainly shared by his poems' intended audience.

Villon's poems are sprinkled with mysteries and hidden jokes. They are peppered with the slang of the time and the underworld subculture in which Villon moved. His works are also replete with private jokes and full of the names of real people – rich men, royal officials, lawyers, prostitutes, and policemen – from medieval Paris.

English translation

Complete works

George Heyer (1869–1925; father of novelist Georgette Heyer) published a translation in 1924. Oxford University Press brought out The Retrospect of Francois Villon: being a Rendering into English Verse of huitains I TO XLI. Of Le Testament and of the three Ballades to which they lead, transl. George Heyer (London, 1924). On 25 December 1924 it was reviewed in The Times Literary Supplement, p. 886 and the review began "It is a little unfortunate that this translation of Villon should appear only a few months after the excellent rendering made by Mr. J. Heron Lepper. Mr. Heyer's work is very nearly as good, however: he makes happy use of quaint words and archaic idioms, and preserves with admirable skill the lyrical vigour of Villon's huitains. It is interesting to compare his version with Mr. Lepper's: both maintain a scholarly fidelity to the original, but one notes with a certain degree of surprise the extraordinary difference which they yet show." George Heyer was a fluent and idiomatic French speaker and the French and English are printed on opposite pages. The book also contains a number of historical and literary notes.

John Heron Lepper published a translation in 1924. Another translation is one by Anthony Bonner, published in 1960. One drawback common to these English older translations is that they are all based on old editions of Villon's texts: that is, the French text that they translate (the Longnon-Foulet edition of 1932) is a text established by scholars some 80 years ago.

A translation by the American poet Galway Kinnell (1965) contains most of Villon's works but lacks six shorter poems of disputed provenance. Peter Dale's verse translation (1974) follows the poet's rhyme scheme.

Barbara Sargent-Baur's complete works translation (1994) includes 11 poems long attributed to Villon but possibly the work of a medieval imitator.

A new English translation by David Georgi came out in 2013. The book also includes Villon's French, printed across from the English. Notes in the back provide a wealth of information about the poems and about medieval Paris. "More than any translation, Georgi's emphasizes Villon's famous gallows humor...his word play, jokes, and puns".

Selections

Translations of three Villon poems were made in 1867 by Dante Gabriel Rossetti. These three poems were "central texts" to Rossetti's 1870 book of Poems, which explored themes from the far past, mid-past, and modern time. Rossetti used "The Ballad of Dead Ladies"; "To Death, of his Lady"; and "His Mother's Service to Our Lady".

W.E. Henley, while editing Slang and its analogues translated two ballades into English criminal slang as "Villon's Straight Tip to All Cross Coves" and "Villon’s Good-Night".

American poet Richard Wilbur, whose translations from French poetry and plays were widely acclaimed, also translated many of Villon's most famous ballades in Collected Poems: 1943–2004.

Where are the snows of yesteryear?

The phrase "Where are the snows of yester-year?" is one of the most famous lines of translated poetry in the English-speaking world. It is the refrain in The Ballad of Dead Ladies, Dante Gabriel Rossetti's translation of Villon's 1461 Ballade des dames du temps jadis. In the original the line is: "Mais où sont les neiges d'antan?" ["But where are the snows of yesteryear?"].

Richard Wilbur published his translation of the same poem, which he titled "Ballade of the Ladies of Time Past", in his Collected Poems: 1943–2004. In his translation, the refrain is rendered as "But where shall last year's snow be found?"

Critical views

Villon's poems enjoyed substantial popularity in the decades after they were written. In 1489, a printed volume of his poems was published by Pierre Levet. This edition was almost immediately followed by several others. In 1533, poet and humanist scholar Clément Marot published an important edition, in which he recognized Villon as one of the most significant poets in French literature and sought to correct mistakes that had been introduced to the poetry by earlier and less careful printers.

In popular culture

Stage

- Justin Huntly McCarthy's 1901 play and novel, If I Were King, presented a romanticized view of Villon, using the “King for a Day” theme and giving the poet a happy ending with a beautiful noblewoman.

- The Vagabond King is a 1925 operetta by Rudolf Friml. Based on McCarthy's play, it was eventually made into two films. (See below.)

- Die Dreigroschenoper (The Threepenny Opera), from 1928, by Kurt Weill and Bertold Brecht, contains several songs that are loosely based on poems by Villon. These poems include "Les Contredits de Franc Gontier", "La Ballade de la Grosse Margot", and "L'Epitaphe Villon". Brecht used German translations of Villon's poems that had been prepared by K. L. Ammer (Karl Anton Klammer), although Klammer was uncredited.

- Daniela Fischerová wrote a play in Czech that focused on Villon's trial called Hodina mezi psem a vlkem—which translates to "Dog and Wolf" but literally translates as "The Hour Between Dog and Wolf". The Juilliard School in New York City mounted a 1994 production of the play, directed by Michael Mayer with music by Michael Philip Ward.

Film and television

- McCarthy's play served as the basis for If I Were King, a 1920 silent film starring William Farnum, and for the 1938 version, adapted by Preston Sturges, directed by Frank Lloyd, and starring Ronald Colman as François Villon, Basil Rathbone as Louis XI and Frances Dee as Katherine.

- Rudolf Friml's operetta, The Vagabond King, was adapted to film in 1930 in a two-strip Technicolor film starring Dennis King and Jeanette MacDonald, and in 1956, to a film starring Oreste Kirkop and Kathryn Grayson.

- McCarthy's play was adapted again in 1945 for François Villon, a French historical drama film directed by André Zwoboda and starring Serge Reggiani, Jean-Roger Caussimon, and Henri Crémieux.

- The television biography François Villon was made in 1981 in West Germany, with Jörg Pleva in the title role.

- On the big screen there was a large co-production France-Germany-Romania made in 1987, a 195 minutes movie Francois Villon - poetul vagabond, directed by renowned Romanian director Sergiu Nicolaescu.

- The Beloved Rogue is a 1927 American silent romantic adventure film starring John Barrymore, Conrad Veidt and Marceline Day, loosely based on Villon's life.

- Villon's work figures in the 1936 movie The Petrified Forest. The main character, Gabby, a roadside diner waitress played by Bette Davis, longs for expanded horizons; she reads Villon and also recites one of his poems to a wandering hobo "intellectual" played by Leslie Howard.

Publications

- Villon's poem "Tout aux tavernes et aux filles" was translated into English by 19th-century poet William Ernest Henley as "Villon’s Straight Tip To All Cross Coves". Another of Henley's attributed poems – written in thieves' slang – is "Villon’s Good-Night".

- The Archy and Mehitabel poems of Don Marquis include a poem by a cat who is Villon reincarnated.

- In Ursula K. Le Guin's short story “April in Paris” (published in 1962), an American professor of medieval French is in Paris researching the unsolved question of how Villon died when he unexpectedly travels in time back to the late 1400s and gets his answer.

- The author Doris Leslie wrote an historical novel, I Return: The Story of François Villon published in 1962.

- In Antonio Skármeta's novel, El cartero de Neruda, Villon is mentioned as having been hanged for crimes much less serious than seducing the daughter of the local bar owner.

- Valentyn Sokolovsky's poem "The night in the city of cherries or Waiting for François" reflects François Villon's life. It takes the form of a person's memories who knew the poet and whose name one can find in the lines of The Testament.

- Italian author Luigi Critone wrote and illustrated a graphic novel based on Villon's life and works. The 2017 book was entitled Je, François Villon [I, François Villon].

- Robert Louis Stevenson's short story "A Lodging for the Night: A Story of Francis Villon" follows the poet into a web of crime and desperation on a snowy November night.

- Hunter Thompson's book on American motorcycle gangs, Hell's Angels (1966) starts with a quote: "I am strong but have no power. I win all yet remain a loser. At break of day I say goodnight. When I lie down I have great fear of falling," which he attributes to Villon.

Music

- His poem Der Erdbeermund was an 1989 single for Culture Beat

- The Belgian violinist Eugène Ysaÿe composed Poème No. 5, "Les neiges d'antan", Op.23, for violin and orchestra, in 1911.

- Claude Debussy set three of Villon's poems to music for solo voice and piano

- French singer Georges Brassens included his own setting of Ballade des dames du temps jadis in his album Le Mauvaise Reputation.

- The Swiss composer Frank Martin's Poèmes de la Mort [Poems of Death] (1969–71) is based on three Villon poems. The work is for the unusual combination of three tenors and three electric guitars.

- Villon was an influence on American musician Bob Dylan.

- Russian singer and songwriter Bulat Okudzhava, composed Prayer for Francois Villon, a very popular song.

- Bulgarian metal band Epizod were inspired by Francois Villon, and based their lyrics on his poems during their early career.

See also

- Le Testament

- List of people who disappeared

References

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Saintsbury, George (1911). "Villon, François". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 87–88. This includes a detailed critical review of the work.

Further reading

- Chaney, Edward F. (1940). The Poems of Francois Villon: Edited and turned into English prose. Oxford Blackwell.

- Freeman, Michael; Taylor, Jane H. M. (1999). Villon at Oxford, The Drama of the Text (in French and English). Amsterdam-Atlanta: Brill Rodopi. ISBN 978-9042004757.

- Holbrook, Sabra (1972). A Stranger in My Land: A Life of François Villon. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux.

- The Poems of François Villon. Translated by Kinnell, Galway. University Press of New England. 1982. ISBN 978-0874512366.

- Lewis, D. Bevan Wyndham (1928). François Villon, A Documented Survey. Garden City, New York: Garden City Publishing.

- Stacpoole, H. De Vere (1916). François Villon: His Life and Times 1431-1463. London: Hutchinson & Co.

- Weiss, Martin (2014), Polysémie et jeux de mots chez François Villon. Une analyse linguistique (e-book) (in French), Vienna, Austria

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

External links

- Villon.org

- Works by François Villon at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about François Villon at Internet Archive

- Works by François Villon at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Société François Villon

- Biography, Bibliography, Analysis, Plot overview (in French)

- Oeuvres complètes de François Villon; Suivies d'un choix des poésies de ses disciples, par La Monnoye et Pierre Janet (in French; complete works, 1867)

- Index entry at Poet's Corner for François Villon

- Illustrations by Lilija Dinere to the book of François Villon Poetry, 1987, «Liesma», Rīga.

- François Villon Ballad about the Plump Margot. French-English parallel text.

- "Epitafio de Villon" o "Balada de los ahorcados" traducido al castellano en Descontexto

Text submitted to CC-BY-SA license. Source: François Villon by Wikipedia (Historical)

If I Were King

If I Were King is a 1938 American biographical and historical film starring Ronald Colman as medieval poet François Villon, and featuring Basil Rathbone and Frances Dee. It is based on the 1901 play and novel, both of the same name, by Justin Huntly McCarthy, and was directed by Frank Lloyd, with a screenplay adaptation by Preston Sturges.

Plot

In Paris, which has long been besieged by the Burgundians, François Villon is the despair of Father Villon, the priest who took him in and raised him from the age of six. Father Villon takes François to mass after his latest escapade (robbing a royal storehouse). There François spies a beautiful woman, Katherine DeVaucelles. Entranced, he tries to strike up an acquaintance, reciting one of his poems (from which the film takes its title) and pretending it was written specially for her. On the surface, she is unmoved, but when soldiers come to take him into custody, she provides him with an alibi.

The crafty King Louis XI of France is in desperate straits and suspects that there is a traitor in his court. He goes in disguise to a tavern to see who accepts an intercepted coded message from the enemy. While there, he is amused by the antics of Villon. The rascal criticizes the king and brags about how much better he would do if he were in Louis' place. When the watch arrives to arrest Villon, a riot breaks out and Villon kills Grand Constable D'Aussigny in the brawl. But when D'Aussigny is revealed as the turncoat, the King is in two minds about what to do with Villon. As a jest, Louis rewards the poet by making him the new Constable, pretending that since nobles have failed in that role, perhaps one of the commoners whom Villon champions can do better.

Villon has fallen in love with Katherine, who is lady-in-waiting on the queen, and she with him, not recognizing him as Villon. Then Louis informs Villon that he intends to have him executed after a week. François soon finds how difficult it is to make the army attack the besieging forces, so, acting on an idea of Katherine’s, he has the King's storehouses release the army's last six months of food to the starving population of Paris—giving the army the same short schedule for attack as the people.

Villon is watched constantly and cannot escape the palace, but when the Burgundians break down the city gates, he escapes to rally the common people to rout them and the defeated enemy then lift the siege. Not knowing the part he has played, Louis has Villon arrested again. It is only when Katherine and Father Villon testify on his behalf that the King realizes what he owes François and goes personally to liberate him.

He and Villon now have some grudging respect for each other, and Villon admits to the King that Louis' job is harder than he once thought. The King on his side now feels obligated to reward Villon again. But wanting less aggravation in his life, Louis decides to pardon Villon only by exiling him from Paris. François leaves on foot, headed for the south of France, but Katherine squeezes this information from Father Villon and follows in her carriage at a discreet distance on the road, waiting for François to tire out.

Cast

- Ronald Colman as François Villon

- Basil Rathbone as King Louis XI

- Frances Dee as Katherine DeVaucelles

- Ellen Drew as Huguette, Villon's girlfriend

- C. V. France as Father Villon

- Henry Wilcoxon as Captain of the Watch

- Heather Thatcher as the Queen

- Stanley Ridges as Rene de Montigny

- Bruce Lester as Noel de Jolys

- Alma Lloyd as Colette

- Walter Kingsford as Tristan l'Hermite

- Sidney Toler as Robin Turgis

- Colin Tapley as Jehan Le Loup

- Ralph Forbes as Oliver le Dain

- John Miljan as Grand Constable Thibaut D'Aussigny

- William Haade as Guy Tabarie

- Adrian Morris as Colin de Cayeulx

- Montagu Love as General Dudon

- Lester Matthews as General Saliere

- William Farnum, as General Barbezier

- Paul Harvey as Burgundian Herald

- Barry Macollum as Storehouse Watchman

- May Beatty as Anna

- Winter Hall as Major Domo

- Francis McDonald as Casin Cholet

- Ann Evers as Lady-in-Waiting

- Jean Fenwick as Lady-in-Waiting

Production

Nine months in France were required to prepare for If I Were King, and the French government cooperated by allowing a replica to be made of the Louvre Palace throne.

Whether Preston Sturges, who at the time was Paramount's top writer, had a collaborator in writing the script is unclear: some early drafts have the name "Jackson" on them as well as Sturges', but the identity of "Jackson" has not been determined. In any event, Sturges finished a draft by February 1938. The final screenplay included Sturges' own original translations of some of Villon's poems.

The film was in production from 12 May to mid-July 1938. Ralph Faulkner, who played a watchman, acted as stunt coordinator and coached the actors on swordplay, and about 900 extras were used for the battle scenes, one of which was cut by the director after the film had opened.

Accolades

If I Were King was nominated for four Academy Awards:

- Supporting Actor - Basil Rathbone

- Art Direction - Hans Dreier and John B. Goodman

- Music, Original Score - Richard Hageman

- Sound, Recording - Loren L. Ryder

Other versions

There is no connection, apart from the title, between the story and the 1852 comic opera by Adolphe Adam called Si j'étais roi (English: If I Were King).

McCarthy's play premiered on Broadway in 1901 and was revived five times up through 1916. It was first adapted in 1920 as a silent film.

In 1925, composer Rudolf Friml and librettists Brian Hooker and W.H. Post turned it into a successful Broadway operetta, The Vagabond King, which featured the songs "Only a Rose", "Some Day", and "Song of the Vagabonds". The operetta was filmed twice - in 1930, starring Jeanette MacDonald and Dennis King and in 1956, directed by Michael Curtiz. Both film versions used very little of Friml's original score.

The François Villon story was also filmed in 1927 under the title The Beloved Rogue, with John Barrymore in the lead role.

The film was adapted as a radio play on Lux Radio Theater October 16, 1939 with Douglas Fairbanks Jr. Academy Award Theater adapted it on May 11, 1946 with Colman reprising his part.

References

External links

- If I Were King at IMDb

- If I Were King at the TCM Movie Database

- If I Were King at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- If I Were King at AllMovie

Streaming audio

- If I Were King on Lux Radio Theater: October 16, 1939

- If I Were King on Academy Award Theater: May 11, 1946

Text submitted to CC-BY-SA license. Source: If I Were King by Wikipedia (Historical)

François Villon (film)

François Villon is a 1945 French historical drama film directed by André Zwoboda and starring Serge Reggiani, Jean-Roger Caussimon and Henri Crémieux. It portrays the life of the fifteenth century writer François Villon. The film was inspired by the play If I Were King by Justin Huntly McCarthy.

Cast

- Serge Reggiani as François Villon

- Jean-Roger Caussimon as Le grand écolier

- Henri Crémieux as Maître Piédoux

- Pierre Dargout as Thibaud

- Guy Decomble as Denisot

- Claudine Dupuis as Huguette du Hainaut

- Jacques-Henry Duval as Tuvache

- Renée Faure as Catherine de Vauselles

- Gabrielle Fontan as La Villonne

- Micheline Francey as Guillemette

- Gustave Gallet as Guillaume de Villon

- Léon Larive as Turgis

- Frédéric Mariotti as Arnoulet

- Albert Michel as Le paysan accusé

- Albert Montigny as Ratier

- Jean Morel as Alain

- Denise Noël as Margot

- Julienne Paroli as La mère

- Marcel Pérès as Le Goliard

- Albert Rémy as Perrot

- Michel Vitold as Noël, le borgne

- Jean Carmet as Un compagnon de François

References

Bibliography

- Harty, Kevin J. The Reel Middle Ages: American, Western and Eastern European, Middle Eastern, and Asian Films about Medieval Europe. McFarland, 1999.

External links

- François Villon at IMDb

Text submitted to CC-BY-SA license. Source: François Villon (film) by Wikipedia (Historical)

The Vagabond King (1956 film)

The Vagabond King is a 1956 American musical film directed by Michael Curtiz and starring Kathryn Grayson, Rita Moreno, Sir Cedric Hardwicke, Walter Hampden, Leslie Nielsen, and Maltese singer Oreste Kirkop in his only feature film role. It was produced and distributed by Paramount Pictures. It is an adaptation of the 1925 operetta The Vagabond King by Rudolf Friml. Hampden plays King Louis XI. Mary Grant designed the film's costumes.

Plot

In fifteenth century France, King Louis XI (Walter Hampden) is besieged in Paris by Charles, Duke of Burgundy, and his allies. Even within the city, Louis' reign is disputed. The irreverent, persuasive beggar poet François Villon (tenor Oreste Kirkop) commands the loyalty of the commoners.

Louis goes in disguise to a tavern to see what sort of a man this poet is. Villon reveals he has no love for the king. Afterward, Louis sees Thibault, his provost marshal, meeting in that very place with Rene, an agent of the Duke of Burgundy. Thibault shows Rene a list of those in Paris who are prepared to overthrow Louis. However, Villon, who has a grudge against Thibault, engages his enemy in a sword fight, during which the incriminating document falls on the floor and is picked up by Louis. The duel is stopped by the city guard. Louis reveals himself and has Villon and his companions thrown into the dungeon. Thibault, however, gets away.

Later, Villon is brought to the king in his unusual garden; the trees bear the bodies of hanged traitors. Louis proposes to let him live, as the new provost marshal, until the Duke of Burgundy is driven away. When Villon turns him down, the king sweetens his offer by including time with Catherine de Vaucelles (Kathryn Grayson), a beautiful noblewoman Villon has fallen in love with and the lives of his friends. Villon accepts, and is introduced to Catherine as "Count François de Montcorbier" from Savoy. Rumor reaches her through her maid, Margaret, that she is to marry the count. She is puzzled at first, then becomes furious when she realizes who her betrothed really is. When she berates Villon for playing a horrible joke on her. He cannot convince her that his love is sincere, while she cannot persuade him that the king is a great man.

Later, Louis' military commander, Antoine de Chabannes, conducts Villon to the dungeon, where he claims the leader of the secret traitors is being held. The turncoat turns out to be de Chabannes himself. Villon is captured, but then rescued when Louis is warned in time by Huguette, who loves Villon. Huguette also warns them that Jehan, a Burgundian agent, is rousing the rabble against Louis in Villon's name. Villon uses the Duke of Burgundy's own scheme against him. When traitors open the city gates to the enemy army, they march in, only to have the gates shut behind them, trapping them inside to be overwhelmed by the commoners under the leadership of Villon. In the fighting, Huguette is killed when she jumps in front of Villon to save him from an archer's arrow. Villon kills both the Duke of Burgundy and Thibault.

Afterward, Villon willingly goes to the gallows to be hanged to fulfill the bargain he made. When the mob becomes outraged, Louis offers to spare Villon if someone will take his place. At the last moment, Catherine offers herself. Then Louis cites a law that spares any man who weds a noblewoman and sets Villon free, confiscating Catherine's wealth to pay for the costs of the war.

Cast

- Kathryn Grayson as Catherine de Vaucelles

- Oreste Kirkop as François Villon

- Rita Moreno as Huguette

- Sir Cedric Hardwicke as Tristan L'Hermite

- Walter Hampden as King Louis XI

- Leslie Nielsen as Thibault

- William Prince as Rene

- Jack Lord as Ferrebouc

- Billy Vine as Jacques

- Vincent Price as the narrator

Music

Music composed by Rudolf Friml, lyrics by Johnny Burke unless otherwise indicated.

- "Bon Jour" - Sung by Oreste Kirkop

- "Vive La You" - Performed by Rita Moreno (dubbed by Eve Boswell) and Vagabonds

- "Some Day" - lyrics by Brian Hooker - Sung by Kathryn Grayson

- "Comparisons" - Sung by Kirkop and Vagabonds

- "Huguette Waltz" - lyrics by Brian Hooker, Sung by Rita Moreno (dubbed by Eve Boswell)

- "Only A Rose" - lyrics by Brian Hooker, presented by Kirkop and Grayson

- "This Same Heart" - sung by Kirkop

- "Watch Out For The Devil" - sung by Kirkop, Grayson and chorus,

danced by ballet dancers at the King's Court

- "Song of the Vagabonds" - from the original operetta, performed by Kirkop, Moreno and Vagabonds

See also

- List of American films of 1956

- The Vagabond King (1930 film)

- The Beloved Rogue, 1927 film

- If I Were King, 1938 film

- Jack Lord filmography

References

External links

- The Vagabond King at the TCM Movie Database

- The Vagabond King at IMDb

- The Vagabond King at AllMovie

Text submitted to CC-BY-SA license. Source: The Vagabond King (1956 film) by Wikipedia (Historical)

The Threepenny Opera

The Threepenny Opera (Die Dreigroschenoper [diː dʁaɪˈɡʁɔʃn̩ˌʔoːpɐ]) is a German "play with music" by Bertolt Brecht, adapted from a translation by Elisabeth Hauptmann of John Gay's 18th-century English ballad opera, The Beggar's Opera, and four ballads by François Villon, with music by Kurt Weill. Although there is debate as to how much, if any, contribution Hauptmann might have made to the text, Brecht is usually listed as sole author.

The work offers a socialist critique of the capitalist world. It opened on 31 August 1928 at Berlin's Theater am Schiffbauerdamm.

With influences from jazz and German dance music, songs from The Threepenny Opera have been widely covered and become standards, most notably "Die Moritat von Mackie Messer" ("The Ballad of Mack the Knife") and "Seeräuberjenny" ("Pirate Jenny").

The Threepenny Opera has been performed in the United Kingdom, the United States, France, Russia, Italy, and Hungary. It has also been adapted to film and radio. The German-language version from 1928 entered the public domain in the US in 2024.

Background

Origins

In the winter of 1927–28, Elisabeth Hauptmann, Brecht's lover at the time, received a copy of Gay's play from friends in England and, fascinated by the female characters and its critique of the condition of the London poor, began translating it into German. Brecht at first took little interest in her translation project, but in April 1928 he attempted to interest the impresario Ernst Josef Aufricht in a play he was writing called Fleischhacker, which he had, in fact, already promised to another producer. Aufricht was seeking a production to launch his new theatre company at the Theater am Schiffbauerdamm in Berlin, but was not impressed by the sound of Fleischhacker. Brecht immediately proposed a translation of The Beggar's Opera instead, claiming that he himself had been translating it . He delivered Hauptmann's translation to Aufricht, who immediately signed a contract for it. Brecht proposed Weill to write the music, and spent the next four months writing the libretto.

Brecht used four songs by the French poet François Villon. Rather than translate the French himself, he used the translations by K. L. Ammer (Karl Anton Klammer), the same source he had been using since his earliest plays.

The first act of both works begins with the same melody ("Peachum's Morning Chorale"/"An Old Woman Clothed In Gray"), but that is the only material Weill borrowed from the melodies Johann Christoph Pepusch arranged for The Beggar's Opera. The title Die Dreigroschenoper was determined only a week before the opening; it had been previously announced as simply The Beggar's Opera (in English), with the subtitle "Die Luden-Oper" ("The Pimp's Opera").

Writing in 1929, Weill made the political and artistic intents of the work clear:

With the Dreigroschenoper we reach a public which either did not know us at all or thought us incapable of captivating listeners ... Opera was founded as an aristocratic form of art ... If the framework of opera is unable to withstand the impact of the age, then this framework must be destroyed ... In the Dreigroschenoper, reconstruction was possible insofar as here we had a chance of starting from scratch.

Weill claimed at the time that "music cannot further the action of the play or create its background", but achieves its proper value when it interrupts the action at the right moments."

Music

Weill's score shows the influence of jazz and German dance music of the time. The orchestration involves a small ensemble with a good deal of doubling-up on instruments (in the original performances, for example, some 7 players covered a total of 23 instrumental parts, though modern performances typically use a few more players).

Premieres

Germany

The Threepenny Opera was first performed at the Theater am Schiffbauerdamm in 1928 on a set designed by Caspar Neher. Despite an initially poor reception, it became a great success, playing 400 times in the next two years. The performance was a springboard for one of the best known interpreters of Brecht and Weill's work, Lotte Lenya, who was married to Weill. Ironically, the production became a great favourite of Berlin's "smart set" – Count Harry Kessler recorded in his diary meeting at the performance an ambassador and a director of the Dresdner Bank (and their wives), and concluded "One simply has to have been there."

Critics did not fail to notice that Brecht had included the four Villon songs translated by Ammer. Brecht responded by saying that he had "a fundamental laxity in questions of literary property."

By 1933, when Weill and Brecht were forced to leave Germany by the Nazi seizure of power, the play had been translated into 18 languages and performed more than 10,000 times on European stages.

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, the first fully staged performance was given on 9 February 1956, under Berthold Goldschmidt, although there had been a concert performance in 1933, and a semi-staged performance on 28 July 1938. In between, on 8 February 1935 Edward Clark conducted the first British broadcast of the work. It received scathing reviews from Ernest Newman and other critics. But the most savage criticism came from Weill himself, who described it privately as "the worst performance imaginable … the whole thing was completely misunderstood". But his criticisms seem to have been for the concept of the piece as a Germanised version of The Beggar's Opera, rather than for Clark's conducting of it, of which Weill made no mention.

United States

America was introduced to the work by the film version of G. W. Pabst, which opened in New York in 1931.

The first American production, adapted into English by Gifford Cochran and Jerrold Krimsky and staged by Francesco von Mendelssohn, featured Robert Chisholm as Macheath. It opened on Broadway at the Empire Theatre, on April 13, 1933, and closed after 12 performances. Mixed reviews praised the music but slammed the production, with the critic Gilbert Gabriel calling it "a dreary enigma".

France

A French version produced by Gaston Baty and written by Ninon Steinhof and André Mauprey was presented in October 1930 at the Théâtre Montparnasse in Paris. It was rendered as L'Opéra de quat'sous; (quatre sous, or four pennies being the idiomatically equivalent French expression for Threepenny).

Russia

In 1930 the work premiered in Moscow at the Kamerny Theatre, directed by Alexander Tairov. It was the only one of Brecht's works to be performed in Russia during his lifetime. Izvestia disapproved: "It is high time that our theatres ceased playing homage to petit-bourgeois bad taste and instead turned to more relevant themes."

Italy

The first Italian production, titled L'opera da tre soldi and directed by Giorgio Strehler, premiered at the Piccolo Teatro in Milan on 27 February 1956 in the presence of Bertolt Brecht. The cast included: Tino Carraro (Mackie), Mario Carotenuto (Peachum), Marina Bonfigli (Polly), Milly (Jenny), Enzo Tarascio (Chief of Police). The conductor was Bruno Maderna. Set designs were by Luciano Damiani and Teo Otto; costume design by Ezio Frigerio.

Hungary

The first Hungarian performance of the play was at the Comedy Theatre of Budapest (Vígszínház), on 6 September 1930. It was titled A koldus operája, which is a reference to Gay's original opera. The play was translated by Jenő Heltai, who mixed Weill and Pepusch' s music, and also Brecht and Gay's texts too. The director was Ernő Szabolcs, the cast included: Pál Jávor (Mackie), Franciska Gaal (Polly), Gerő Mály (Peachum), Ella Gombaszögi (Mrs. Peachum).

Roles

Synopsis

Overview

Set in Victorian London, the play focuses on Macheath, an amoral antihero who leads a criminal gang, committing robbery, arson, rape and murder.

Macheath ("Mackie," or "Mack the Knife") marries Polly Peachum. This displeases her father, who controls the beggars of London, and he endeavours to have Macheath hanged. His attempts are hindered by the fact that the Chief of Police, Tiger Brown, is Macheath's old army comrade. Still, Peachum exerts his influence and eventually gets Macheath arrested and sentenced to hang. Macheath escapes this fate via a deus ex machina moments before the execution when, in an unrestrained parody of a happy ending, a messenger from the Queen arrives to pardon Macheath and grant him the title of baron. The details of the original 1928 text have often been substantially modified in later productions.

A draft narration by Brecht for a concert performance begins: "You are about to hear an opera for beggars. Since this opera was intended to be as splendid as only beggars can imagine, and yet cheap enough for beggars to be able to watch, it is called the Threepenny Opera."

Prologue

A street singer entertains the crowd with the illustrated murder ballad or Bänkelsang, titled "Die Moritat von Mackie Messer" ("Ballad of Mack the Knife"). As the song concludes, a well-dressed man leaves the crowd and crosses the stage. This is Macheath, alias "Mack the Knife".

Act 1

The story begins in the shop of Jonathan Jeremiah Peachum, the boss of London's beggars, who outfits and trains the beggars in return for a slice of their takings from begging. In the first scene, the extent of Peachum's iniquity is immediately exposed. Filch, a new beggar, is obliged to bribe his way into the profession and agree to pay over to Peachum 50 percent of whatever he made; the previous day he had been severely beaten up for begging within the area of jurisdiction of Peachum's protection racket.

After finishing with the new man, Peachum becomes aware that his grown daughter Polly did not return home the previous night. Peachum, who sees his daughter as his own private property, concludes that she has become involved with Macheath. This does not suit Peachum at all, and he becomes determined to thwart this relationship and destroy Macheath.

The scene shifts to an empty stable where Macheath himself is preparing to marry Polly once his gang has stolen and brought all the necessary food and furnishings. No vows are exchanged, but Polly is satisfied, and everyone sits down to a banquet. Since none of the gang members can provide fitting entertainment, Polly gets up and sings "Seeräuberjenny", a revenge fantasy in which she is a scullery maid turning pirate queen to order the execution of her bosses and customers. The gang becomes nervous when the Chief of Police, Tiger Brown, arrives, but it's all part of the act; Brown had served with Mack in England's colonial wars and had intervened on numerous occasions to prevent the arrest of Macheath over the years. The old friends duet in the "Kanonen-Song" ("Cannon Song" or "Army Song"). In the next scene, Polly returns home and defiantly announces that she has married Macheath by singing the "Barbarasong" ("Barbara Song"). She stands fast against her parents' anger, but she inadvertently reveals Brown's connections to Macheath which her parents subsequently use to their advantage.

Act 2

Polly warns Macheath that her father will try to have him arrested. He is finally convinced that Peachum has enough influence to do it and makes arrangements to leave London, explaining the details of his bandit "business" to Polly so she can manage it in his absence. Before he leaves town, he stops at his favorite brothel, where he sees his ex-lover, Jenny. They sing the "Zuhälterballade" ("Pimp's Ballad", one of the Villon songs translated by Ammer) about their days together, but Macheath doesn't know Mrs Peachum has bribed Jenny to turn him in. Despite Brown's apologies, there's nothing he can do, and Macheath is dragged away to jail. After he sings the "Ballade vom angenehmen Leben" ("Ballad of the Pleasant Life"), another Villon/Ammer song, another girlfriend, Lucy (Brown's daughter) and Polly show up at the same time, setting the stage for a nasty argument that builds to the "Eifersuchtsduett" ("Jealousy Duet"). After Polly leaves, Lucy engineers Macheath's escape. When Mr Peachum finds out, he confronts Brown and threatens him, telling him that he will unleash all of his beggars during Queen Victoria's coronation parade, ruining the ceremony and costing Brown his job.

Act 3

Jenny comes to the Peachums' shop to demand her money for the betrayal of Macheath, which Mrs Peachum refuses to pay. Jenny reveals that Macheath is at Suky Tawdry's house. When Brown arrives, determined to arrest Peachum and the beggars, he is horrified to learn that the beggars are already in position and only Mr Peachum can stop them. To placate Peachum, Brown's only option is to arrest Macheath and have him executed. In the next scene, Macheath is back in jail and desperately trying to raise a sufficient bribe to get out again, even as the gallows are being assembled.

Soon it becomes clear that neither Polly nor the gang members can, or are willing to, raise any money, and Macheath prepares to die. He laments his fate and poses the 'Marxist' questions: "What's picking a lock compared to buying shares? What's breaking into a bank compared to founding one? What's murdering a man compared to employing one?" (These questions did not appear in the original version of the work, but first appeared in the musical Happy End, another Brecht/Weill/Hauptmann collaboration, in 1929 – they may in fact have been written not by Brecht, but by Hauptmann).

Macheath asks everyone for forgiveness ("Grave Inscription"). Then a sudden and intentionally comical reversal: Peachum announces that in this opera mercy will prevail over justice and that a messenger on horseback will arrive ("Walk to Gallows"); Brown arrives as that messenger and announces that Macheath has been pardoned by the queen and granted a title, a castle and a pension. The cast then sings the Finale, which ends with a plea that wrongdoing not be punished too harshly as life is harsh enough.

Musical numbers

Prelude

11. Ouverture

12. Die Moritat von Mackie Messer ("The Ballad of Mack the Knife" – Street singer)

Act 1

13. Morgenchoral des Peachum (Peachum's Morning Choral – Peachum, Mrs Peachum)

14. Anstatt dass-Song (Instead of Song – Peachum, Mrs Peachum)

15. Hochzeits-Lied (Wedding Song – Four Gangsters)

16. Seeräuberjenny (Pirate Jenny – Polly)

17. Kanonen-Song (Cannon Song – Macheath, Brown)

18. Liebeslied (Love Song – Polly, Macheath)

19. Barbarasong (Barbara Song – Polly)

10. I. Dreigroschenfinale (First Threepenny Finale – Polly, Peachum, Mrs Peachum)

Act 2

11.a Melodram (Melodrama – Macheath)

11a. Polly's Lied (Polly's Song – Polly)

12.a Ballade von der sexuellen Hörigkeit (Ballad of Sexual Dependency – Mrs Peachum)

13.a Zuhälterballade (Pimp's Ballad or Tango Ballad – Jenny, Macheath)

14.a Ballade vom angenehmen Leben (Ballad of the Pleasant Life – Macheath)

15.a Eifersuchtsduett (Jealousy Duet – Lucy, Polly)

15b. Arie der Lucy (Aria of Lucy – Lucy)

16.a II. Dreigroschenfinale (Second Threepenny Finale – Macheath, Mrs Peachum, Chorus)

Act 3

17.a Lied von der Unzulänglichkeit menschlichen Strebens (Song of the Insufficiency of Human Struggling – Peachum)

17a. Reminiszenz (Reminiscence)

18.a Salomonsong (Solomon Song – Jenny)

19.a Ruf aus der Gruft (Call from the Grave – Macheath)

20.a Grabschrift (Grave Inscription – Macheath)

20a. Gang zum Galgen (Walk to Gallows – Peachum)

21.a III. Dreigroschenfinale (Third Threepenny Finale – Brown, Mrs Peachum, Peachum, Macheath, Polly, Chorus)

Reception

Opera or musical theatre?

The ambivalent nature of The Threepenny Opera, derived from an 18th-century ballad opera but conceived in terms of 20th-century musical theatre, has led to discussion as to how it can best be characterised. According to critic and musicologist Hans Keller, the work is "the weightiest possible lowbrow opera for highbrows and the most full-blooded highbrow musical for lowbrows".

The Weill authority Stephen Hinton notes that "generic ambiguity is a key to the work's enduring success", and points out the work's deliberate hybrid status:

For Weill [The Threepenny Opera] was not just 'the most consistent reaction to [Richard] Wagner'; it also marked a positive step towards an operatic reform. By explicitly and implicitly shunning the more earnest traditions of the opera house, Weill created a mixed form which incorporated spoken theatre and popular musical idioms. Parody of operatic convention – of Romantic lyricism and happy endings – constitutes a central device.

"Mack the Knife"

The work's opening and closing lament, "Die Moritat von Mackie Messer," was written just before the Berlin premiere, when actor Harald Paulsen (Macheath) threatened to quit if his character did not receive an introduction; this creative emergency resulted in what would become the work's most popular song, later translated into English by Marc Blitzstein as "Mack the Knife", and now a jazz standard that Louis Armstrong, Bobby Darin, Ella Fitzgerald, Sonny Rollins, Frank Sinatra, Peggy Lee, Michael Bublé, Robbie Williams and countless others have performed. In 2015, the Library of Congress added the recordings of "Mack the Knife" by Louis Armstrong and Bobby Darin to the National Recording Registry. It has been named one of the hundred most popular songs of the twentieth century.

In 1986, American fast-food chain McDonald's launched an advertising campaign featuring a new mascot "Mac Tonight" loosely based on the lyrics "Mack the Knife" featuring a parody of the song. The advert, which was associated with a 10% increase in later diners in some Californian restaurants at the time, led to a lawsuit by Bobby Darin's son, Dodd Mitchell Darin. The lawsuit concerned the parody created by McDonald's stated that it was in violation of copyright law. The case was settled outside of court without requiring a court hearing. Following this the mascot was mostly dropped from McDonalds marketing.

"Pirate Jenny"

"Pirate Jenny" is another well-known song from the work, which has since been recorded by Nina Simone, Judy Collins, Tania Tsanaklidou, and Marc Almond, among others. In addition, Steeleye Span recorded it under the alternative title "The Black Freighter". Recently, the drag queen Sasha Velour has made an adaptation by the same name for an installment of One Dollar Drags, an anthology of short films.

"The Second Threepenny Finale"

Under the title "What Keeps Mankind Alive?", this number has been recorded by the Pet Shop Boys on the B-side of their 1993 single "Can You Forgive Her?", and on two albums. Tom Waits covered it on two albums, and William S. Burroughs performed it in a 1994 documentary.

Revivals

Germany

After World War II the first stage performance in Berlin was a rough production of The Threepenny Opera at the Theater am Schiffbauerdamm. Wolf Von Eckardt described the 1945 performance where audience members climbed over ruins and passed through a tunnel to reach the open-air auditorium deprived of its ceiling. In addition to the smell of dead bodies trapped beneath the rubble, Eckardt recollects the actors themselves were "haggard, starved, [and] in genuine rags. Many of the actors ... had only just been released from concentration camp. They sang not well, but free." Barrie Kosky produced the work again at the Theater am Schiffbauerdamm in 2021. The production travelled to the Ruhrfestspiele in 2022, the Internationaal Theater Amsterdam, Teatro Argentina, Rome, the Edinburgh International Festival in 2023, and to the 2024 Adelaide Festival.

France

The Pabst film The Threepenny Opera was shown in its French version in 1931. In 1937 there was a production by Ernst Josef Aufricht at the Théâtre de l'Étoile which failed, though Brecht himself had attended rehearsals. The work was not revived in France until after World War II.

United Kingdom

In London, West End and Off-West End revivals include:

- Royal Court Theatre, 9 February to 20 March 1956 and Aldwych Theatre, from 21 March 1956. Directed by Sam Wanamaker. With Bill Owen as Macheath, Daphne Anderson as Polly.

- Prince of Wales Theatre and Piccadilly Theatre, opening 10 February 1972. With Vanessa Redgrave, Diana Quick and Barbara Windsor.

- National Theatre (Olivier Theatre), 13 March 1986. New translation by Robert David MacDonald, directed by Peter Wood. With Tim Curry as Macheath, Sally Dexter as Polly, Joanna Foster as Lucy and Eve Polycarpou (Adam) as Jenny.

- Donmar Warehouse, 1994. Translation by Robert David MacDonald (book) and Jeremy Sams (lyrics). With Tom Hollander as Macheath and Sharon Small as Polly. This production released a cast recording as was nominated for Best Musical Revival and Best Supporting Performance in a Musical (for Tara Hugo as Jenny) at the 1995 Laurence Olivier Awards.

- National Theatre (Cottesloe Theatre) and UK Tour, February 2003. Translation by Jeremy Sams (lyrics) and Anthony Meech (book), directed by Tim Baker.

- National Theatre (Olivier Theatre), 18 May to 1 October 2016. New adaptation by Simon Stephens, directed by Rufus Norris. With Rory Kinnear as Macheath, Rosalie Craig as Polly, Nick Holder as Peachum, Haydn Gwynne as Mrs Peachum (nominated for Best Actress in a Supporting Role in a Musical at the 2017 Laurence Olivier Awards), Sharon Small as Jenny, Peter de Jersey as Brown. This production was broadcast live to cinemas worldwide through NT Live on 22 September.

In 2014, the Robert David MacDonald and Jeremy Sams translation (previously used in 1994 at the Donmar Warehouse) toured the UK, presented by the Graeae Theatre Company with Nottingham Playhouse, New Wolsey Theatre Ipswich, Birmingham Repertory Theatre and West Yorkshire Playhouse.

United States

In 1946, four performances of the work were given at the University of Illinois in Urbana, and Northwestern University gave six performances in 1948 in Evanston, Illinois. In 1952, Leonard Bernstein conducted a concert performance of the work at the Brandeis University Creative Arts Festival in the Adolph Ullman Amphitheatre, Waltham, Massachusetts, to an audience of nearly 5,000. Marc Blitzstein, who translated the work, narrated.

At least five Broadway and Off-Broadway revivals have been mounted in New York City.

- In 1956, Lotte Lenya won a Tony Award for her role as Jenny, the only time an off-Broadway performance has been so honored, in Blitzstein's somewhat softened version of The Threepenny Opera, which played Off-Broadway at the Theater de Lys in Greenwich Village for a total of 2,707 performances, beginning with an interrupted 96-performance run in 1954 and resuming in 1955. Blitzstein had translated the work into English, and toned down some of its acerbities. Over the course of its run, the production featured Scott Merrill as Macheath; Edward Asner as Mr. Peachum; Charlotte Rae (later Carole Cook, billed as Mildred Cook, then Jane Connell) as Mrs. Peachum; Jo Sullivan Loesser as Polly; Bea Arthur as Lucy; Jerry Orbach as PC Smith, the Street Singer and Mack; John Astin as Readymoney Matt/Matt of the Mint; and Jerry Stiller as Crookfinger Jake.

- A nine-month run in 1976–77 had a new translation by Ralph Manheim and John Willett for Joe Papp's New York Shakespeare Festival at the Vivian Beaumont Theater at Lincoln Center, directed by Richard Foreman, with Raul Julia as Macheath, Blair Brown as Lucy, and Ellen Greene as Jenny. The production rescinded some of Blitzstein's modifications. Critics were divided: Clive Barnes called it "the most interesting and original thing that Joe Papp ... has produced" whilst John Simon wrote "I cannot begin to list all the injuries done to Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill's masterpiece."

- A 1989 Broadway production, billed as 3 Penny Opera, translated by Michael Feingold, starred Sting as Macheath. Its cast also featured Georgia Brown as Mrs Peachum, Maureen McGovern as Polly, Kim Criswell as Lucy, KT Sullivan as Suky Tawdry and Ethyl Eichelberger as the Street Singer. The production was unsuccessful.

- Liberally adapted by playwright Wallace Shawn, the work was brought back to Broadway by the Roundabout Theatre Company at Studio 54 in March 2006 with Alan Cumming playing Macheath, Nellie McKay as Polly, Cyndi Lauper as Jenny, Jim Dale as Mr Peachum, Ana Gasteyer as Mrs Peachum, Carlos Leon as Filch, Adam Alexi-Malle as Jacob and Brian Charles Rooney as a male Lucy. Included in the cast were drag performers. The director was Scott Elliott, the choreographer Aszure Barton, and, while not adored by the critics, the production was nominated for the "Best Musical Revival" Tony award. Jim Dale was also Tony-nominated for Best Supporting Actor. The run ended on June 25, 2006.

- The Brooklyn Academy of Music presented a production directed by Robert Wilson and featuring the Berliner Ensemble for only a few performances in October 2011. The play was presented in German with English supertitles using the 1976 translation by John Willett. The cast included Stefan Kurt as Macheath, Stefanie Stappenbeck as Polly and Angela Winkler as Jenny. The Village Voice review said the production "turn[ed] Brecht and Weill's middle-class wake-up call into dead entertainment for rich people. His gelid staging and pallid, quasi-abstract recollections of Expressionist-era design suggested that the writers might have been trying to perpetrate an artsified remake of Kander and Ebb's Cabaret.

Regional productions include one at the Williamstown Theatre Festival, Massachusetts, in June and July 2003. Directed by Peter Hunt, the musical starred Jesse L. Martin as Mack, Melissa Errico as Polly, David Schramm as Peachum, Karen Ziemba as Lucy Brown and Betty Buckley as Jenny. The production received favorable reviews.

Film adaptations

German director G. W. Pabst made a 1931 German- and French-language version simultaneously, a common practice in the early days of sound films.

Another version, Die Dreigroschenoper, was directed by Wolfgang Staudte in West Germany in 1963, starring Curd Jürgens as Macheath, Hildegard Knef as Jenny, Gert Fröbe as Peachum, and Sammy Davis Jr. as Moritat singer.

In 1989 an American version (renamed Mack the Knife) was released, directed by Menahem Golan, with Raul Julia as Macheath, Richard Harris as Peachum, Julie Walters as Mrs Peachum, Bill Nighy as Tiger Brown, Julia Migenes as Jenny, and Roger Daltrey as the Street Singer.

Radio adaptations

In 2009, BBC Radio 3 in collaboration with the BBC Philharmonic broadcast a complete radio production of the Michael Feingold translation directed by Nadia Molinari with the music performed by the BBC Philharmonic. The cast included Joseph Millson as Macheath, Elen Rhys as Polly/Whore, Ruth Alexander-Rubin as Mrs Peachum/Whore, Zubin Varla as Mr. Peachum/Rev. Kimball, Rosalie Craig as Lucy/Whore, Ute Gfrerer as Jenny, Conrad Nelson as Tiger Brown and HK Gruber as the Ballad Singer.

Recordings

Recordings are in German, unless otherwise specified.

- Die Dreigroschenoper, 1930, on Telefunken. Abridged/incomplete. Lotte Lenya (Jenny), Erika Helmke (Polly), Willy Trenk-Trebitsch (Macheath), Kurt Gerron (Moritatensänger; Brown), and Erich Ponto (Peachum). Lewis Ruth Band, conducted by Theo Mackeben. Released on CD by Teldec Classics in 1990.

- The Threepenny Opera, 1954, on Decca Broadway 012–159–463–2. In English. Lyrics by Marc Blitzstein. The 1950s Broadway cast, starring Jo Sullivan (Polly Peachum), Lotte Lenya (Jenny), Charlotte Rae (Mrs Peachum), Scott Merrill (Macheath), Gerald Price (Street Singer), and Martin Wolfson (Peachum). Bea Arthur sings Lucy, normally a small role, here assigned an extra number. Complete recording of the score, without spoken dialogues. Conducted by Samuel Matlowsky.

- Die Dreigroschenoper, 1955, on Vanguard 8057, with Anny Felbermayer, Hedy Fassler, Jenny Miller, Rosette Anday, Helge Rosvaenge, Alfred Jerger, Kurt Preger and Liane Augustin. Vienna State Opera Orchestra conducted by F. Charles Adler.

- Die Dreigroschenoper, 1958, on CBS MK 42637. Lenya, who also supervised the production, Johanna von Koczian, Trude Hesterberg, Erich Schellow, Wolfgang Neuss, and Willy Trenk-Trebitsch, Arndt Chorus, Sender Freies Berlin Orchestra, conducted by Wilhelm Brückner-Rüggeberg. Complete recording of the score, without spoken dialogues.

- Die Dreigroschenoper, 1966, conducted by Wolfgang Rennert on Philips. With Karin Hübner, Edith Teichmann, Anita Mey, Hans Korte, Dieter Brammer, and Franz Kutschera.

- The Threepenny Opera, 1976, on Columbia PS 34326. Conducted by Stanley Silverman. In English, new translation by Ralph Manheim and John Willett. Starring the New York Shakespeare Festival cast, including Raul Julia (Macheath), Ellen Greene (Jenny), Caroline Kava (Polly), Blair Brown (Lucy), C. K. Alexander (Peachum) and Elizabeth Wilson (Mrs Peachum)

- Die Dreigroschenoper, 1968, on Polydor 00289 4428349 (2 CDs). Hannes Messemer (MM), Helmut Qualtinger (P), Berta Drews (MsP), Karin Baal (Polly), Martin Held (B), Hanne Wieder (J), Franz Josef Degenhardt (Mor). Conducted by James Last. The only recording, up to the present, that contains the complete spoken dialogue.

- Die Dreigroschenoper, 1988, on Decca 430 075. René Kollo (Macheath), Mario Adorf (Peachum), Helga Dernesch (Mrs Peachum), Ute Lemper (Polly), Milva (Jenny), Wolfgang Reichmann (Tiger Brown), Susanne Tremper (Lucy), Rolf Boysen (Herald). RIAS Berlin Sinfonietta, John Mauceri.

- Die Dreigroschenoper, 1990, on Koch International Classics 37006. Manfred Jung (Macheath), Stephanie Myszak (Polly), Anelia Shoumanova (Jenny), Herrmann Becht (Peachum), Anita Herrmann (Mrs Peachum), Eugene Demerdjiev (Brown), Waldemar Kmentt (Street Singer); Bulgarian Television and Radio Mixed Choir and Symphony Orchestra, Victor C. Symonette

- The Threepenny Opera, 1994, on CDJAY 1244. In English. Donmar Warehouse (London) production. Translated by Robert David Macdonald (lyrics translated by Jeremy Sams). Conducted by Gary Yershon. With Sharon Small (Polly Peachum), Tara Hugo (Jenny), Natasha Bain (Lucy Brown), Tom Hollander (Macheath), Simon Dormandy (Tiger Brown), Beverley Klein (Mrs Peachum) and Tom Mannion (Mr Peachum).

- Die Dreigroschenoper, 1997, on Capriccio. Conducted by Jan Latham-König, with Ulrike Steinsky, Gabriele Ramm, Jane Henschel, Walter Raffeiner, Rolf Wollrad, and Peter Nikolaus Kante.

- Die Dreigroschenoper, 1999, BMG 74321 66133–2, Ensemble Modern, HK Gruber (conductor, Mr Peachum), Max Raabe (Macheath), Sona MacDonald (Polly), Nina Hagen (Mrs Peachum), Timna Brauer (Jenny), Hannes Hellmann (Tiger Brown)

See also

- Threepenny Novel (1934)

- Story adapted to Brazilian scenario by Chico Buarque, having Rio instead of London, as Ópera do Malandro (1979)

- The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, Volume III: Century

Notes

References

Sources

- Brook, Stephen, ed. (1996). Opera: A Penguin Anthology. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-026073-1.

- Casaglia, Gherardo (2005). "Die Dreigroschenoper (31 August 1928)". L'Almanacco di Gherardo Casaglia (in Italian).

- Haas, Michael; Uekermann, Gerd (1988). Zu unserer Aufnahme (Booklet accompanying the 1988 recording, Cat: 430-075). London: Decca Record Company.

- Hinton, Stephen (1990). Kurt Weill: The Threepenny Opera. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-33026-8.

- Hinton, Stephen (1992). "Dreigroschenoper, Die". Grove Music Online (8th ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.O006155. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0.

- Ross, Alex (2008). The Rest Is Noise. London: Fourth Estate. ISBN 978-1-84115-475-6.

- Taruskin, Richard (2010). Music in the Early Twentieth Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-538484-0.

- Thomson, Peter; Sacks, Glendyr, eds. (1994). The Cambridge Companion to Brecht. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-42485-1.

External links

- Threepenny Opera at the Internet Broadway Database

- The Threepenny Opera at the Internet Off-Broadway Database

- Die Dreigroschenoper, Kurt Weill Foundation for Music

- Information on The Threepenny Opera English version, marc-blitzstein.org

- Mack the Knife (1989) at IMDb

Text submitted to CC-BY-SA license. Source: The Threepenny Opera by Wikipedia (Historical)

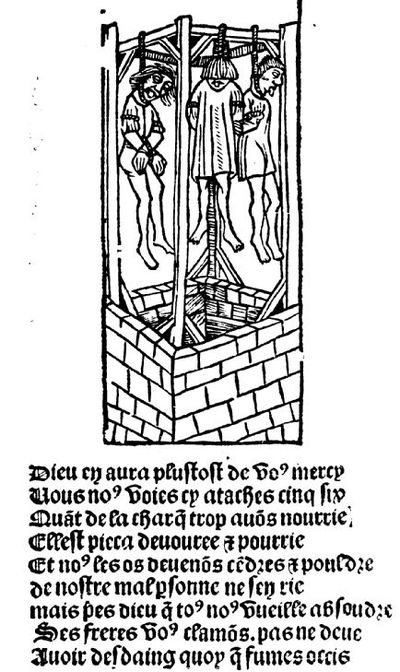

Ballade des pendus

The Ballade des pendus, literally "ballad of the hanged", also known as Epitaphe Villon or Frères humains, is the best-known poem by François Villon. It is commonly acknowledged, although not clearly established, that Villon wrote it in prison while he awaited his execution. It was published posthumously in 1489 by Antoine Vérard.

Title

In the Coisline manuscript, this ballade has no title, and in the anthology Le Jardin de Plaisance et fleur de rethoricque printed in 1501 by Antoine Vérard, it is just called Autre ballade (literally, "Another ballad"). It is titled Épitaphe Villon in the Fauchet manuscript and in Pierre Levet's 1489 edition, and it is called Épitaphe dudit Villon in the Chansonnier de Rohan. In his 1533 commented edition, Clément Marot names it: Épitaphe en forme de ballade, que feit Villon pour luy & pour ses compaignons s'attendant à estre pendu avec eulx, which translates approximately to: Epitaph in the form of a ballad, which Villon made for him & for his companions expecting to be hanged with them. The modern title is due to the romantics and is problematic because it reveals the identity of the narrators too early and compromises the effect of surprise desired by Villon.

The title Epitaph Villon and its derivatives are also improper and confusing, because Villon had already written a real epitaph for himself at the end of Testament (around 1884 to 1906). Moreover, this title (and in particular the Marot's version) implies that Villon composed the work while awaiting his hanging, remains in question.

Villon's historians and commentators have now mostly resolved to designate this ballad by its first words: Frères humains (literally, "Human brothers"), as is customary when the author has assigned no title.

The title Ballade des pendus subsequently given to this ballad is all the less appropriate since there already exists a ballad with that title by Théodore de Banville, in his one-act play Gringoire (1866). This ballad has been renamed Le Verger du Roi Louis, but that is not the title given by the author either.

Context

It is often said that Villon composed this ballade while awaiting his execution following the Ferrebouc affair, in which a papal notary was injured in a brawl with Villon and his friends. In support of this point of view, Gert Pinkernell underlines the desperate and macabre nature of the text and concludes that Villon must have composed it in prison. However, as Claude Thiry notes: “It is a possibility, but among others: we cannot completely exclude it, but we should not impose it.” He remarks indeed that it is far from the only text of Villon which refers to his fear of the gallows and to the dangers which await lost children. The Ballades en jargon, for example, contain many allusions to the gallows, but they were not necessarily composed during his imprisonment. Moreover, Thiry points out that, if we disregard the modern title, the poem is an appeal to Christian charity towards the poor more than towards the hanged, and, unlike the large majority of Villon's texts, the poet does not present this one as autobiographical. In addition, the macabre character of the ballad is not unique to it, as it is also found in the evocation of the mass grave of the innocents from stanzas CLV to CLXV of the Testament .

Background

This poem is an appeal to Christian charity, a highly respected value in the Middle Ages (as seen in the third and fourth lines of the first stanza: "For, if you take pity on us poor fellows, God will sooner have mercy on you."). Redemption is at the heart of the ballad. Villon recognizes that he has focussed too much care of his physical being to the detriment of his spirituality. This observation is reinforced by the very raw description of the rotting bodies (probably inspired by the macabre spectacle of the mass grave of the innocents) which contrasts with the religious themes of the poem. The hanged first exhort passers-by to pray for them, then in the final stanza, the prayer is extended to all humans.

Form

The poem is in the form of a large ballade (3 dizains and 1 quintil, with decasyllabic verses)

- All lines have 10 syllables.

- The last line is the same in each stanza.

- The first three stanzas have 10 lines, and the last has 5 lines.

- Each stanza has the same rhyme scheme.

- There are several enjambments.

Text of the ballad with English translation

The translation deliberately follows the original as closely as possible.

French Source:, English source:

References

External links

- (in French) Livres audio mp3 gratuits 'Ballade des pendus' de François Villon - (Association Audiocité).

- Sung version of the poem performed by Serge Reggiani, composed by Louis Bessières (on YouTube).

- Sung version of the poem performed by Anika Kildegaard, composed by Jean-François Charles (on YouTube).

Text submitted to CC-BY-SA license. Source: Ballade des pendus by Wikipedia (Historical)

The Adventures of François Villon

The Adventures of François Villon was a series of four silent films released in 1914, directed by Charles Giblyn and featuring Murdock MacQuarrie as François Villon. The four films are The Oubliette, The Higher Law, Monsieur Bluebeard, and The Ninety Black Boxes. The films were based on a series of short stories about François Villon written by George Bronson Howard.

The Oubliette

The Oubliette was released in August 1914 and features Murdock MacQuarrie and Lon Chaney. This film and By the Sun's Rays are two of Chaney's earliest surviving films.

Cast of The Oubliette

- Murdock MacQuarrie as François Villon

- Pauline Bush as Philippa de Annonay

- Lon Chaney as Chevalier Bertrand de la Payne

- Doc Crane as King Louis XI

- Chester Withey as Colin

- Millard K. Wilson as Chevalier Philip de Soisson

- Agnes Vernon

The Higher Law

The Higher Law was released in September 1914 and features Murdock MacQuarrie and Pauline Bush. Lon Chaney also has a role. The film is now considered to be lost.

Cast of The Higher Law

- Murdock MacQuarrie as François Villon

- Pauline Bush as Lady Eleyne

- Doc Crane as King Louis XI

- Lon Chaney as Sir Stephen

- Millard K. Wilson

- Chester Withey

- William B. Robbins

Monsieur Bluebeard

Monsieur Bluebeard was released in October 1914 in two reels.

The Ninety Black Boxes

The Ninety Black Boxes was released in November 1914 in two reels and features Murdock MacQuarrie and Doc Crane.

References

External links

- The Oubliette at IMDb

- The short film The Oubliette is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.

- The Higher Law at IMDb

Text submitted to CC-BY-SA license. Source: The Adventures of François Villon by Wikipedia (Historical)

Ballade des dames du temps jadis

The "Ballade des dames du temps jadis" ("Ballade of Ladies of Time Gone By") is a Middle French poem by François Villon that celebrates famous women in history and mythology, and a prominent example of the ubi sunt? genre. It is written in the fixed-form ballade format, and forms part of his collection Le Testament in which it is followed by the Ballade des seigneurs du temps jadis.

The section is simply labelled Ballade by Villon; the title des dames du temps jadis was added by Clément Marot in his 1533 edition of Villon's poems.

Translations and adaptations

Particularly famous is its interrogative refrain, Mais où sont les neiges d'antan?, an example of the ubi sunt motif, which was common in medieval poetry and particularly in Villon's ballads.

This was translated into English by Rossetti as "Where are the snows of yesteryear?", for which he popularized the word "yesteryear" to translate Villon's antan. The French word was used in its original sense of "last year", although both antan and the English yesteryear have now taken on a wider meaning of "years gone by". The phrase has also been translated as "But where are last year's snows?".

The ballade has been made into a song (using the original Middle French text) by French songwriter Georges Brassens, and by the Czech composer Petr Eben, in the cycle Šestero piesní milostných (1951).

Text of the ballade, with literal translation

The text is from Clement Marot's Œuvres complètes de François Villon of 1533, in the Le Grand Testament pages 34 to 35.

In popular culture

The refrain Mais où sont les neiges d'antan? has been quoted or alluded to in numerous works.

- In Der Rosenkavalier (1911), the opera by Richard Strauss to an original German libretto by Hugo von Hofmannsthal, the Marschallin asks, in her monologue toward the end of Act 1 as she considers her own, younger self: “Wo ist die jetzt? Ja, such' dir den Schnee vom vergangenen Jahr!” (“Where is she now? Yes, look for the snow of yesteryear.”)

- In Bertolt Brecht's 1936 play Die Rundköpfe und die Spitzköpfe (Round Heads and Pointed Heads), the line is quoted as "Wo sind die Tränen von gestern abend? / Wo is die Schnee vom vergangenen Jahr?" ("Where are the tears of yester evening? / Where are the snows of yesteryear?") in "Lied eines Freudenmädchens" (Nannas Lied) ("Song of a joy-maiden [prostitute]" (Nanna's song)); music originally by Hanns Eisler, alternative arrangement by Kurt Weill.

- The original 1945 manuscript of the play, “The Glass Menagerie” by Tennessee Williams, contains optional stage directions for projecting the legend “Où sont les neiges d’antan?” on a screen during Amanda’s monologue in Scene One where she recounts her (likely exaggerated) past life as a popular Southern belle.

- The poem was alluded to in Joseph Heller's novel Catch-22, when Yossarian asks "Where are the Snowdens of yesteryear?" in both French and English, Snowden being the name of a character who dies despite the efforts of Yossarian to save him.

- Umberto Eco quotes the line "Where are the snows of yesteryear?" in the final chapter "Last Page" of The Name of the Rose.

- James O'Barr wrote "Oú sont les neiges d'antan Villon" in his 1981 graphic novel The Crow" under an image of The Crow lying broken hearted and empty.

- In S2:E9 of Downton Abbey, the Dowager Countess of Grantham, played by Dame Maggie Smith, quotes the refrain "Mais où sont les neiges d'antan?" in its original French, when referring to the father of the present Lord "Jinks" Hepworth, who she knew in the 1860s.

See also

- Le Testament

- François Villon

- Ballade des pendus

Notes

References

Text submitted to CC-BY-SA license. Source: Ballade des dames du temps jadis by Wikipedia (Historical)

Owlapps.net - since 2012 - Les chouettes applications du hibou